Someone at work asked “do you wanna see a mostly complete solar farm, but it’s somewhere cold and muddy?” to which I asked “Can I touch the big power things” They looked at me funny and said “they aren’t powered on yet, so probably, just don’t get all weird about it.”

Dear reader, I was only partially weird about it.

Traveling up

This Solar farm is one of a complex of plants being built in Lincolnshire. As someone Norfolk born and raised, it pains me to see weirdarse fenlanders getting money for things.

The Fens are miles away from London, both in terms of distance, and chromosomal diversity. This means we have to catch a train if we want to make a day trip of it. I therefore meet my colleagues at King’s Cross station. I marvel at the new concourse. Its much brighter than the old one, and makes it look much more Victorian. Hard approve.

Whilst we were waiting I noticed a massive bird of prey wafting around. I found the keeper and had a chat, hes a Harris Hawk who’s about 13 years old. As it was a cold day, he wasn’t in the mood to murder pigeons, which was a bit of a shame. Still it was great to see a falconer falconing.

You should hold a bird of prey, its great.

Fast train

We took the Avanti train Harrogate, which I assumed would be slow & dirty like most suburban trains. Surprisingly, it’s smooth, clean and fast, getting us to Grantham in just an hour and ten minutes. It turns out that fast rail is a good thing after all. (Insert your own witty observation about HS2)

As we waited for a taxi, there was an announcement on the platform tannoy: the “Sir Nigel Gresley” would be going past in the next 15 minutes. This explained the abundance of train nerds milling about on the platform. I’m not going to lie, I fucking love me a steam train, so I lobbied to wait for the drive by.

I wasn’t disappointed, the thing rolled in at full blast, tooting away like Thomas the Tank engine.

You should go and touch steam trains.

Muddy Field Time

The taxi arrives, drives us past the birthplace of Maggie Thatcher, noted milk snatcher and ice creme enthusiast. We marvel at the local sights, including, but not limited to: pound land, Aldi & Spa.

Eventually we arrive at the site. We are asked to sign in by the security guard on the gate. We do our safety briefing: Lots of detail which probably has depressingly predictable causes (you must reverse park, I bet there is a story or two behind that). Once complete we got a briefing about the equipment on site, and what were we were going to see.

This was the first time that I witnessed the scale of the solar plant. This thing is about 6 fields of former grazing land. In all it’s rated at about 50-70MW. The site is _vast_. However it looks smaller than it is, because all the hedgerows and trees have been kept.

One of the interesting problems for construction is fixing land drains after piling the structures for the panels. Turns out fields get muddy if you don’t have land drains. Mind you, without the use of pesticides to control the vegetation, I suspect that worms will eventually sort some of that water buildup out.

In the mean time water collects, and needs to be managed. This is causing a headache for the site managers, especially as its winter and rain is happening again, finally. From an ecological point of view, it’s pleasing to see standing water in a farmer’s field that’s not green with run-off juiced algae.

This is just one field. The rolls of cable on the right are about 2 meters high. You’ll probably need to open that image larger to see the panels.

Aggregating power

Inverters and transformers are expensive. So it makes sense to connect as many panels as possible together into one inverter. to that end panels are joined up in series, so they generate something like 300 – 400v DC rather than the native 24-48v (the exact number depends on a bunch of factors but let’s say 14) This has a number of benefits, but the biggest one is requiring smaller cables for the same amount of power transmission. (Power = current * voltage, so 10kw at 24v requires much thicker cables than 10kw at 240v)

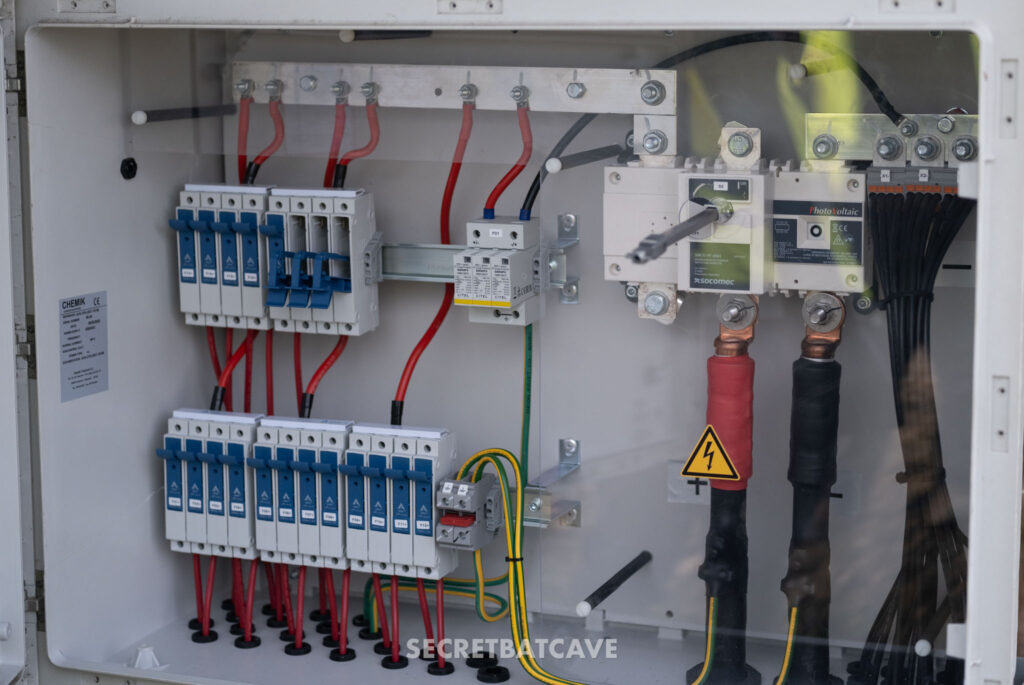

Panels wired in series are called “strings”. These strings are joined together in combiner boxes (see below) In contrast, solar panels on houses are more than likely to have a single micro inverter for each panel. You can potentially get more power, but it can cost double.

This is what a combiner box looks like:

Each string is connected to a fuse (left), then joined together to a common bus (right) which is sent to the nearest inverter. In this box there are 16 strings of panels joined in one combiner. More fancy boxes have current sensors in them.

Using napkin maths, ( I forgot to ask for the exact numbers) those cables are transporting something like 60-90kw of power at peak.

Those combiners are fed into the local inverters.

The inverters(grey boxes left and right) convert DC solar into AC. That AC is then stepped up to 33KV by the transformer in the green cage. The transformer apparently has a cooling oil supply, which joins all of these transformers together. I assume its for cooling, but I didn’t ask.

Big machinery

As the site is not live, it means that I get to go into places that normally require lots of paper work and qualifications to get access to. Here I am inside the compound that contains the 33kv-132kv transformer.

The cables come up from the inverters and are fed into overhead bus bars. They feed into the big white box that is the transformer. This thing is the size of a semi detached house.

This is the side view. There are two sections; on the left the part owned by national grid, on the right, the bit owned by us.

On the left is the platform that sends the power to the grid via the pylon. Just to the right of the first wooden post is the circuit breaker. Obviously its a lot bigger than the ones you have at home. It stands about 3 meters high.

The “cables” (scaffolding poles) are raised up to the first set of switches. This lifts the cable over the fence (we’ll get back to that later) to the compound that contains our equipment.We also have a set of switches. After the switches are the meters. This allows us to work out how much power we are pushing into the grid.

Finally there are some thin surge arresters, and then the white step-up transformer on the far right.

Now, the compound that’s owned by the national grid has a massive Electric fence around it, making it look like something out of Jurassic Park:

But what I’m not really understanding is what the electric fence is for. I mean sure its there to deter people getting in, but there are cables that have 132kv of pocket lighting just waiting to boil you in 0.1 of a second. I can’t help that thinking its like putting guard dogs around the edge of a lion enclosure.

Here is a glimpse in the control room. I love the sexy labels on the panels. These are designed to be around for a long time. All of these devices are designed to monitor and control the transformer and cutoff systems.

This is the side of the big step up transformer. The temperature sensors are analog, as are what appears to be the cutoff levels. There isn’t much power to this transformer, so its not very warm today.

Conclusions

Big infrastructure is sexy as fuck. If you get the opportunity to go and see something like this,don’t ask questions, just go. Go and touch something large and expensive. Just make sure you wrap up warm. It was cold as balls that day.

As a fake infrastructure engineer (ie I piss about on AWS for a living) its great to see actual machinery, and look at how they monitor the optimal running of large and expensive devices.

The penalties for running the transformers, inverters or any other equipment out of spec is large and smokey. For example, the transformer/inverter units have a oil loop to keep them cool and dielectric. If that fails not only do you need a new inverter, you’ll also have to pay a fine for dumping oil into the environment.

Caution is the name of the game here, and that pleases me. Big bits of machinery, engineered up to a standard, not shat out to meet some quarterly personal bonus goal.